Imperial War Museum

Duxford

An amazing day out

January 26th 2022

A crystal clear, cold day in the flatlands of Cambridgeshire.

I’m with my mate John who has bother with his mobility. His body has taken a battering from his life as a plumber (and rugby and motorcycling and cricket). He has a wheely walker, which I mention only because there will be a lot of walking today, a couple of miles minimum I would think. I think secretly neither of us is sure how he’ll cope.

We enter a pristine, glass-walled hall where we check in. We’re welcomed by a smiling, considerate red-coat volunteer who helps us through the process and explains about the shuttle bus that will help us get around. This chap is genuinely interested to get our visit off to a good start. He seems to know we are in for a special few hours, he has a confident, knowing look about him as if he’s saying, ‘prepare to be amazed’.

Through a gate and we’re into a large shop. We will exit this way too.

Yes, twice through the shop. Going in, I find it rather ‘commercial’. By the time I come out, over five hours later, I simply cannot resist buying something to remember an extraordinary day.

A hundred yard walk to Hanger One called Air Space. I’m not a great one for spoiling a surprise so don’t look at the guide leaflet. Through a door and……… we’re faced with a dozen Spitfires. Frankly it takes my breath away. We’ve all heard of them and doubtless seen them, at least on television or film, but to see them here, live gives me the goose bumps. It’s pretty emotional actually.

My initials are on this Spitfire!

My Dad. Back right July 1938.

The plane is an Avro Tutor

My Dad trained at Duxford in 1938, so being here at all is a touching experience.

Many medical students were deemed to have 'Pacifict Leanings' so were ejected from military training. However, my Dad went on to further training (I am still searching records) possibly Northolt, and served throughout the war attaining the rank of Squadron Leadrer in 1944.

When I see a life-size photo of Douglas Bader today here at Duxford, with whom my Dad played golf, it’s a direct link back all those years.

Surprisingly, to me anyway, there have been twenty-four incarnations or ‘Marks’ of Spitfires. From Mark 1, first flown on 26th May 1940 powered by a Rolls Royce Merlin engine to Mark 24, with its supercharged Griffon 61 engine. The wings on the latest Marks were redesigned to cope with the extra power and the cockpit now has a ‘teardrop’ canopy. These, plus a number of other minor changes, saw the latest evolution fly 90 MPH faster than the Mark 1.

Standing next to one they feel substantial. See one flying in the distance or against another aircraft they are small. Small, yet a colossus among fighting machines. Well up there in the pantheons of iconic aircraft.

In the adjoining hall there’s more open-mouthed stuff. A Lancaster, a Vulcan and Concorde. Walking among the planes is extraordinary, they are huge. I’ve seen and heard the Lancaster fly overhead, such a distinctive growl. There are only two airworthy, one in the UK, one in Canada. The Vulcan’s flying days are over but we can walk beneath and look up int the bomb bay. And what a size those wings. I walk through Concorde back to front. It’s narrow inside, like a horizontal rocket. The vast majority of passengers had no idea how much it cost to fly because their companies paid to get them over to the USA in under three hours. The cockpit has a bewildering array of buttons and switches. It amazes me that she made her first flight over fifty years ago. Our engineering skills, imagination and ingenuity created a legend.

Also, in here is the Mosquito, hanging from the roof. She has a wonderful view of the Lancaster and Concorde below. It’s a wooden aircraft and perhaps more modest to look at, but I think it’s what my Dad mainly flew in, so it is part of my pilgrimage.

We ask a red-coat to summon transport for us. Sounds pompous, but it’s not just us, they do it for anybody! The little electric bus takes us to the south end of the site, a least half a mile away. Hangar 8 is the Land Warfare Exhibition. From here we’ll work our way slowly back to the shop.

I remember visiting the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds. I told a fellow visitor I was astonished at the scope and variety of weapons.

‘We have to be able to defend ourselves,’ he said to me.

I pointed out that if we hadn’t invented so many ways to attack each other we wouldn’t need so many means of defence.

‘You have a point I suppose,’ he said.

It feels the same in Hangar 8 where there are tanks, artillery, transport and supply vehicles. A film of the D-Day Landing, taped noises of bombs going off and landscaped areas depicting where soldiers suffered. In many ways it’s the huge battle tanks that grab my attention, I remember classic names such as Chieftain and Centurion. Today’s battle tank is the Challenger, which is a pretty awesome piece of kit. Someone has a thing about tank names beginning with ‘C’.

Tanks began as basic, armoured units in WW1. First was the prototype Little Willie (also known as ‘Mother’). Sixteen tonnes of steel with a crew of 5 or 6. Two to drive and the rest to act as gunners. It never saw combat but set the whole concept of tanks off.

The first ‘real’ tank was The British Mark 1, rhomboidal in shape where the tracks run right round each side of the vehicle, allowing it to traverse wide tranches on the WW1 battlefields. The problem was with the early ones was that they could basically only shoot in the direction they were pointing. In other words, they didn’t have rotating turret.

Renault built the FT, the first tank with a rotating, armed and armoured turret. The vast majority of tanks to follow copied this design. French flair!

A walk in the sun with the odd plane buzzing around to our right, and we come to the American Air Museum.

In the café near the entrance, we have a very good cup of coffee and an horrific sausage roll.

Fortunately, the display of planes was incredible.

We enter the building at first floor level so as we look, planes are both on the ground below and strung up on wires above. The first thing we see is the nose of a B52 bomber looking straight at us. Stretching out sideways two enormous wings each supporting four engines and a 1000 gallon fuel tank. The total wingspan is 56 metres. Which is seven metres more than the plane’s length. Quite simply it is huge. The wings are so long and heavy they have extra wheels three quarters of the way along.

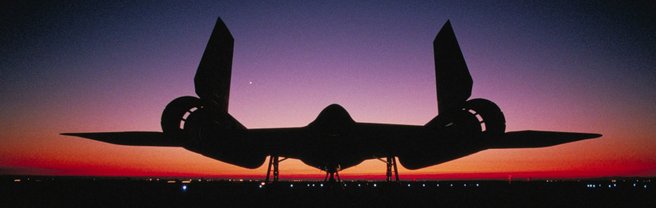

Then there’s the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird. This is one of the planes I particularly wanted to see because I first saw it about fifty years ago at Farnborough Air Show. My uncle took me and it made a lasting impression. He wouldn’t have known back then, but my uncle helped me create a memory that would literally last a lifetime.

It just shows how important it is to create special moments for youngsters.

The aircraft is a black, menacing thing, but weirdly beautiful.

In the late 1950s, the call came from on high to build a plane with the following characteristics:

- ‘…that can’t be shot down’.

- Fly for long periods in excess of Mach 3 (2,301,81 mph). (It still holds the record).

- Be undetectable to radar.

- Withstand 1000 degree temperatures on leading edges due to air friction. (That temperature would melt a conventional air frame).

- Fly at 85,000 feet (faster and higher than any missile aimed to bring it down).

It’s creators, ‘Skunk Works’ (pseudonym for Lockheed Martin's Advanced Development Programs) said, ‘everything had to be invented. Everything.’

It’s an amazing achievement considering it was conceived back in the late 1950s and first flew in 1962. It was something right at the forefront of new technology, in fact, new technology was developed to build it.

Another iconic American plane is the A-10 Thunderbolt, affectionately known as The Warthog. It’s a strong, stocky aircraft with twin engines mounted high on the rear. It bristles with menace and is most widely known for its fearsome 30mm gatling gun mounted in the nose cone.

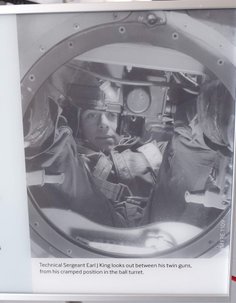

One thing gives me the creeps is the lower gun turret slung below planes like the B17 and B24. It’s exposed and so cramped that the operator has to crunch up. There isn’t even room for him to wear a parachute. If there is damage, the door to the plane from the turret might not even open. I’m claustrophobic and not great with heights so this job is my worst nightmare. YUK!

Duxford of course was a ‘live’ airfield during the war. Today, as we walk round in the sun enjoying the peace and quiet, it’s easy to forget that during the Battle of Britain, hundreds and hundreds of sorties would have flown from here. Each time, some didn’t return. Douglas Bader said, ‘You lived very much on the surface. If you took it to heart when people you’d been having breakfast with didn’t come back at 11 o’clock, you could never have got on.. You aren’t any less conscious of losing someone but… one has to get on with the job. You have this protective skin – what one calls understatement – which is in the British character…. and it’s easily acquired.’

In the next hangar, conservation work is constantly on the go, protecting historical aircraft and equipment for future generations. They try not to be too intrusive and keep the aircraft as original as possible. There’s a faint smell of oil and fuel and people, some staff, some volunteers, beaver away on engines or whatever else needs repair or service.

In the ‘Flying Aircraft’ hangar (this means they are still airworthy) engineers restore and maintain privately owned aircraft, mainly smaller planes, including Hurricanes which played such a crucial role alongside the Spitfire.

There’s also a B17 Flying Fortress, The Memphis Belle, undergoing service. The cowlings are off exposing the workings of the four powerful rotary engines.

In WW11 the aircraft carrier came to prominence and in the Air and Sea hangar there are planes such as the Fairey Gannet and Hawker Siddeley Buccaneer which took to sea, then flight. The Gannet was particularly interesting because it had two propellors, one behind the other, which contra-rotated (spun in opposite directions). Each prop had its own engine and they could be independently turned off to conserve fuel. A Gannet made the first ever landing by a turbo-prop plane on an aircraft carrier in June 1950.

There’s a Japanese torpedo. Big devil too at 9 metres long. It was oxygen-propelled and carried 500 kg (1210 lb) of explosive. I had another uncle who was torpedoed twice and survived twice but the experiences left their mark on him psychologically for life – as it would. Very nasty.

Another craft on show, that also would not suit me, is a German one-man submarine, called a Beaver (biber in German). More claustrophobia. Submarines in general caused enormous loss but the one-man versions were less successful with technical flaws and poorly trained crews.

So, after five hours, we head back towards the shop. I pop into hangar one again because I’d forgotten to take photos of the mosquito on which my Dad flew. While I’m back in there I sneak a last look at the Spitfires. And then Concorde, and the Lancaster and the Vulcan, just to make sure I hadn’t been dreaming earlier.

Two further things left an impression. Firstly, a Rolls Royce Trent engine sitting on a stand in splendid isolation. The current Rolls Royce aero engine. It was developed to power the Boeing 777 and it is a huge thing. The diameter of the intake is 2.79 metres or 9 ft 2 ins. The engine is nearly 5 metres long.

Finally, as I head out, the thing that really gives me the creeps, more than anything else in the whole place, a Polaris Missile. It is nearly 10 metres long and 1.37 m diameter. They would be fired out of a Submarine by compressed air then a two-stage solid rocket would take over. It would accelerate to 7000 mph and have a range of 2,800 miles. It carries three 200 kiloton nuclear warheads, each one of the three 16 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. In the 1960s submarines took over from aircraft to handle our nuclear deterrent. The Polaris was the UKs deterrent from 1968 to 1994 and four Resolution-class submarines carried 16 missiles each. The thought of these things lurking beneath the waves is the stuff of nightmares.

I bought a T-shirt. One depicting the Lockheed Blackbird, not only did it bring back a 50-year memory, it is also a hugely impressive aircraft. Not sure what it thought of sharing a hangar with those damn sausage rolls, but there we are.

Finally, thank you to the red-coat volunteers who are helpful, knowledgeable and polite.

Thank you also to all the people who keep this place going – it is quite extraordinary.

As we drive away, I’m reminded of something a friend of mine once said, ‘that’s another day they can’t take off us.’